Human rights management system – our work in practice

Respecting and promoting human rights are at the very core of Finnfund’s work as a development financier and responsible impact investor.

Respecting and promoting human rights are at the very core of Finnfund’s work as a development financier and responsible impact investor.

Finnfund uses the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights (UNGPs) as the framework for the management of potential adverse human rights impacts and has embedded a human right perspective into its investment process from initial due diligence to the exit including environmental and social risk management.

Finnfund appraises all medium-to-high environmental and social risk investments against the IFC Performance Standards (IFC PS) and the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (also known as ILO Core Labour Standards, ILO CLS) as the reference framework for environmental and social management. We may also use certain sector-specific standards, such as Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Global Good Agricultural Practice (Global GAP).

Our human rights approach is one element of our Sustainability Policy and described in our Human Rights Statement but it is also strongly linked to our wider sustainability and impact approach and to our aim to promote Sustainable Development Goals such as gender equality and decent work. Finnfund also has an exclusion list that addresses some potential human rights impacts.

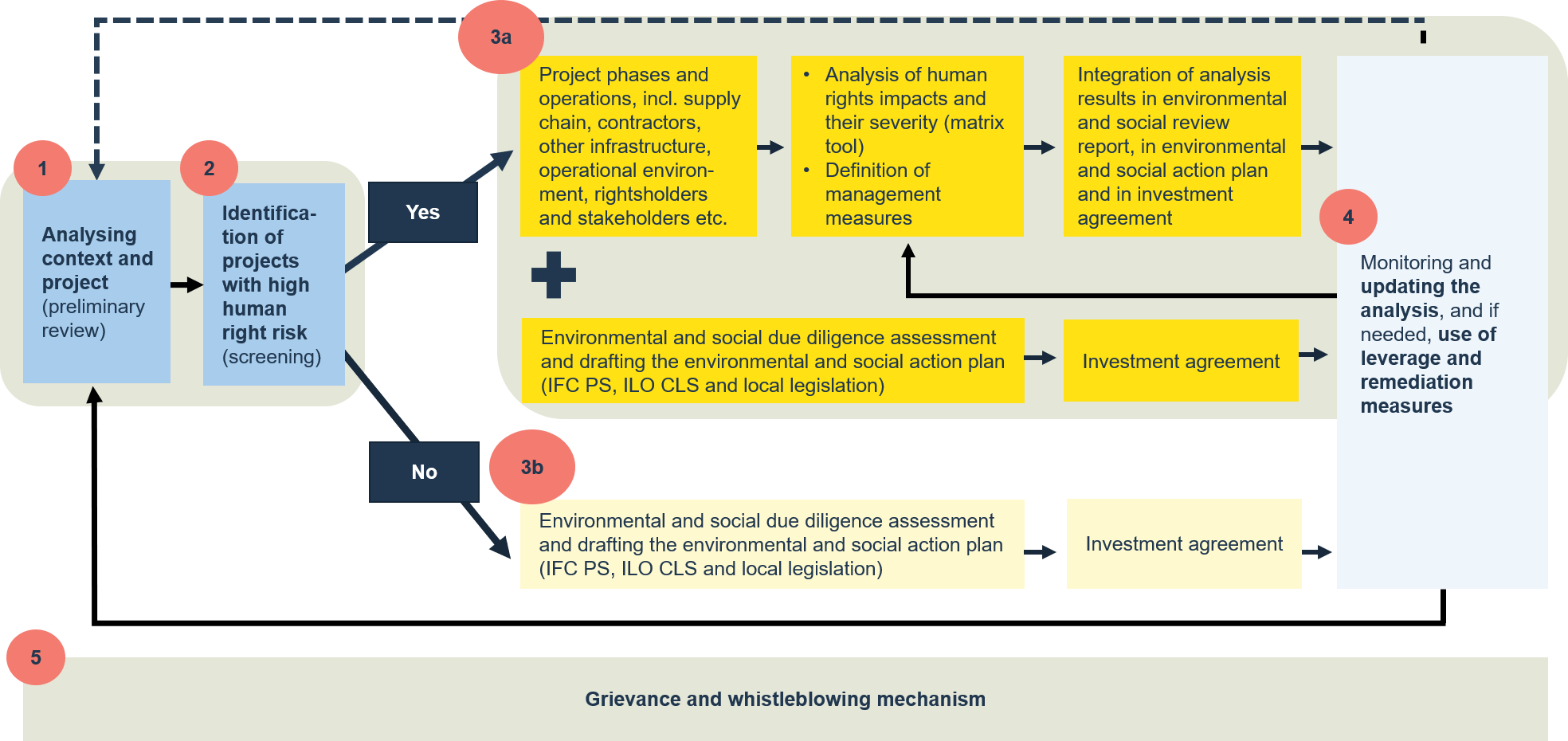

In this article we explain, step-by-step, how our human rights due diligence works in practice and how we identify the projects that require human rights assessments going beyond what is covered in the IFC PS and the ILO CLS. The processes and tools continue to be developed and our approach is evolving.

Human rights risk screening is the backbone

The IFC Performance Standards address human rights such as the rights to land, cultural rights, workers’ rights, rights to health, safety and security, as well as indigenous peoples’ rights. Still, when compared with the UNGP framework, some human rights or rights holders are not covered as comprehensively as others. The context of an individual investment may also worsen the potential human rights impacts of an investment.

Therefore, a human rights risk screening of each investment and their context forms the backbone of our approach to human rights due diligence.

It is important to note, that in this article, likewise within the UNGP framework, the term human rights due diligence refers to the management system of potential human rights impacts during the entire investment period. While traditionally, in the field of financing, the meaning of due diligence is limited to only one phase of the investment process, i.e. the analysis done prior to the investment decision, as shown in the picture below.

The main aim of our human rights due diligence is to:

- identify and prioritise the investments with potential human rights-related risks for which our processes need to go beyond the normal IFC PS and ILO CLS framework,

- implement processes for identifying, assessing, monitoring and addressing the potential human rights impacts caused by Finnfund’s investments.

The scope and depth of Finnfund’s assessment of potential human rights impacts is always determined on a case-by-case basis depending on the results of the first screening, the context and severity of potential negative human rights impacts and sector specific risks of the activity to be financed.

“As a development financier, our duty is to go there where we are needed the most and where our financing can generate positive impacts. The nature and complexity of the financed activities in challenging geographies, imply that while there is great potential for positive impact, there is also a potential for adverse human rights risks and impacts that can be severe. This is what we need to work with.”

“As a development financier, our duty is to go there where we are needed the most and where our financing can generate positive impacts. The nature and complexity of the financed activities in challenging geographies, imply that while there is great potential for positive impact, there is also a potential for adverse human rights risks and impacts that can be severe. This is what we need to work with.”

– Sylvie Fraboulet-Jussila, Senior Environmental and Social Adviser

1. Preliminary review: Familiarising with the project and the context

A preliminary review of the project and context from a human rights point of view marks the beginning of the appraisal process in which Finnfund assesses the potential investments against three criteria: profitability, sustainability, and impact. The preliminary review is done prior to the clearance in principle decision (CIP), i.e. the moment in our investment process when we determine if a more in-depth appraisal of a potential investment can be started. Projects that do not receive clearance in principle are rejected.

Because of its mandate as a development financier, Finnfund typically invests in challenging countries, often with limited political and civic rights. Therefore, at this stage, we aim to understand how a specific context within the country in question and which of its elements and phases may increase the impact a project can have on the rights of people.

At this early stage, our assessment is based mainly on limited information provided by the project proponent, and public sources including information published by local and international Human Rights organisations and other stakeholders, or media searches. Sources of information include e.g. the CIVICUS Monitor Index and watch list on situation of the civic space, the Freedom House Democracy Index, reports and annual global analysis from Front Line Defenders, human rights reports published by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch or the US Department of State, and information from the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre.

In practice, phases 1-2 are combined in the same human rights screening tool.

2. Screening: Identification of projects and contexts with potential human rights impacts

Projects and contexts with potential human rights impacts are identified first before an investment decision and then again during the entire investment process as part of annual monitoring and ad hoc – whenever any human rights related concerns may rise.

In practice, screening means that the project and context is assessed against a list of criteria to find out whether the need to extend the scope of the project’s human rights appraisal beyond the normal environmental and social framework (IFC PS and ILO CLS) is triggered or not triggered.

This screening tool –a “human rights trigger list” – helps identify contextual issues, such as conflict or post-conflict situations, limited political freedoms, risks to human rights defenders or high levels of corruption, which could exacerbate our investments’ potential human rights impacts. It also includes criteria related to the project, the project company, the business relationships and the products. The trigger list is regularly updated.

Going through the trigger list means looking for answers to questions such as

- Is the project located in fragile/post-conflict/dictatorship or authoritarian/high corruption countries?

- Are there risks for human rights defenders?

- Is there state-sponsored discrimination/repression of certain groups?

- Is there well-known past or present opposition of the populations to the project/sector?

- Is the project located in a region / country where migrant workers are often present / used as a labour force? If yes, are there well-known issues related to them?

- Is the project located in areas suffering from water scarcity and is the project using or impacting significant volumes of water?

- Do the sponsors (founders of the project) have negative human rights track record?

- Is the project in ICT, fintech, healthcare and other sectors handling confidential client data?

- Does the project have legacy of negative human rights impacts?

- What is the level of commitment and/or capacity of the sponsor to manage potential human rights impacts? Does the company have previous experience of managing similar risks in similar contexts?

- Does the project / investee have direct project partners with negative human rights track record, e.g. contractors, suppliers, clients, joint venture partners?

- Is the project/activity in sectors associated with specific supply chain issues (e.g. child or forced labour)?

- Does the project/company have close relationship with existing high Human Rights risk businesses/operations operated by third parties (e.g. captive power production for a controversial activity)?

- Is the project / company government owned or are there associated facilities (e.g. transmission line, road) to be constructed for the project by the government or another third party and that could have significant human rights impacts?

- Can the products or services be misused or used in an unintended way or constitute a potential safety/health risk for the users?

3.a) Triggered project

If the project IS “triggered” it means that there are elements in the project, in the business relationships or in context that may result in human rights impacts and risks that are not addressed within the scope of the “standard” environmental and social appraisal and management framework (IFC PS and ILO CLS).

In such a case Finnfund’s environmental and social advisors will adapt their work in assessing, prioritising, and monitoring these specific aspects and defining management measures depending on the specific project and context. It can range from commissioning a specific human rights impact assessment of the supply chain to enhancing the scope of an environmental and social impact assessment, to focusing discussions with the project management or stakeholders on certain aspects, from assessing compliance with additional standards (for example the Client Protection Principles) to using Finnfund’s in house human rights impact matrix and severity tool or a combination of several approaches.

The results of the assessment are included into the Environmental and Social review documents, and the mitigation measures are integrated into the Environmental and Social Action Plan (ESAP) that the project company will have to implement, and finally, into the investment agreement. In the investment agreements there are also some general human rights clauses, for instance, regarding the compliance of the operational grievance mechanisms with the UNGP’s efficiency criteria and the development of human rights policies.

Depending on the reasons why a given project is “triggered” the mitigation measures will vary. For example, a context that limits freedom of assembly or freedom of expression means that the company’s stakeholder engagement may have to take innovative forms such as small group discussions, or use of survey tools. Or a company that is likely to be associated with significant human rights impacts in their supply chain may have to focus on building a robust supply chain management system, with strict supplier selection criteria, and eventually take measures to bar some suppliers.

Finnfund will not finance a company associated with past serious human rights impact and not demonstrating a commitment to improve.

Regardless of the results of the human rights screening, the environmental and social risk of every potential investment is categorised and appraised against the IFC PS and the ILO CLS as applicable. The appraisal determines whether the project or the company complies with the applicable standards, and if not, what are the improvements it must implement to become compliant within a reasonable time.

Because the IFC PS and ILO CLS address certain human rights for certain stakeholders – such as labour rights (IFC PS2, ILO CLS), right to own land and to an adequate standard of living (IFC PS2; PS5 for projects that may entail forced physical or economic displacement; PS number 6 for projects with impacts on ecosystem services), the right to safety, health and security (PS4) – our standard environmental and social appraisal will cover potential impacts on those human rights.

Example 1: Finnfund considered a potential investment in a company X that uses recycled paper as a raw material. Due to the contextual risk of child labour and health and safety issues in that country’s recycling sector, Finnfund requested that external experts perform a supply chain human rights assessment. One of the screening’s output was a supply chain human rights action plan, detailing management and mitigation measures, which the client committed to implement. Finnfund decided to invest in the company and is now monitoring the implementation of the human rights action plan.

3.b) Not triggered

If the project is NOT triggered it means that we have not identified elements in the project, in the business relationships or in context that may result in human rights impacts and risks that would not be addressed within the scope of the standard environmental and social appraisal and management framework (IFC PS and ILO CLS).

Such a project will undergo a standard environmental and social appraisal process, that tackles certain human rights impacts as explained above. However, situations and contexts can change so also non-triggered projects will be re-screened as a minimum on an annual basis to capture such changes and react to them.

Example 2: An energy project is located in a country that is affected by water scarcity. However, the energy production process does not require water. Further, the country is not regarded as challenging from a human rights point of view and other criteria of the human rights screening list are not triggerred. Therefore the project has been assessed against the IFC PS and ILO CLS framework as part of the standard appraisal process.

Example 3: Finnfund has invested in a forestry company in an area that, in principle, is not challenging from a human rights point of view. The investment was not triggered in our human rights screening hence we applied our standard environmental and social management procedures based on IFC PS and ILO CLS. Because of the challenging labour and working conditions and potential high risks to the health and safety of workers associated with the forestry sector, we put a significant emphasis on assessing and monitoring the compliance and performance of the company against the IFC PS2 (on labour and working conditions) and on ensuring safe and healthy working conditions for all people involved in their operations. The focus on labour issues translated into clear contractual Environmental & Social requirements, including a reference to the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) standard. These requirements and monitoring together with a strong commitment from the company have led to considerable reduction of accidents and incidents and improvements of occupational health and safety.

4. Monitoring

All our investments are monitored, based on quarterly or annual reports, regular discussions with our clients, site visits, external audits, consultants, and other information channels such as media monitoring. The investees are also expected to inform Finnfund in case of accidents or other significant changes in their situation.

As a minimum, in preparation for each project’s annual review, Finnufund’s environmental and social advisor updates the information on the project, its progress in addressing environmental, social and human rights issues identified at the time of investment and towards compliance with the applicable international standards and re-screens the investment against the criteria of the screening list (phase 1–2).

If there are any indications that the situation may have changed and/or negative human rights impacts have occurred, the analysis is updated, and the companies are required to take corrective actions accordingly.

If something happens…

What then if actual adverse impacts on human rights occur? Finnfund is committed to take steps and use our influence to have the impact on human rights addressed by the entity that has caused the impact or contributed to it, in most cases the investee or the company they have a business relationship with. In all these cases we must bear in mind Finnfund’s degree of connection to the impact and its possibilities to exercise and increase its leverage on the investees. The grievance mechanisms mentioned above are important to promote effective access to remedy for those who have been harmed.

Remedies can take different forms depending on the context, the situation, the type and severity of the impact on human rights, etc and be escalated. The views of the affected rights-holders must be voiced, heard, and considered in determining the appropriate form of remedy.

Example 4: In 2015, before Finnfund developed the human rights screening process, we invested in a garment manufacturer using polyester and cotton fabrics imported from different Asian countries. At the time of investment, Finnfund required that the company improves their supplier management system. Recently, because of concerns regarding the deteriorating human rights situation of minorities in a given region, we checked with the company whether they could be, via their fabric suppliers, linked with such human rights impacts. The information indicates that the company is not sourcing from such suppliers.

5. Grievance and whistleblowing

Finnfund’s investees are also required, as appropriate, to have an effective operational-level grievance mechanism to facilitate non-judicial access to remedy for internal and external stakeholders. The grievance mechanisms are expected to meet at least the criteria defined in the IFC PS, and over time, the efficiency criteria of the UNGP Principle 31.

In addition to these grievance mechanisms, Finnfund has its own grievance and whistleblowing mechanism, which includes a specific internal procedure and a team tasked with assessing and responding to the grievances.

This means that rights-holders and stakeholders from different groups can report through Finnfund’s website or via telephone or email, any concerns over suspicion of abuse or human right infringements, either in Finnfund’s own operations or connected with any of the companies financed. Grievances can be made anonymously. Rights-holders and stakeholders can also discuss directly with Finnfund’s representatives, for example in connection with monitoring visits.

Example 5: As part of Finnfund’s requirements set in the investment agreement, a company X developed a Human Resources (HR) Policy and internal and external grievance systems based on IFC Performance Standards. During the third year of investment, the company received a complaint through their whistleblowing channel: according to someone there had been unfair recruitment and promotion practices. The company reported this to Finnfund. The company HR Policy and manual included these issues, and all staff was supposed to be aware of the correct practices and employee rights after the induction process. The management took the complaint very seriously: an External HR consultant was hired to investigate and found alleged issues correct. The persons involved were treated according to local labour law and company HR policy. All staff was informed about the actions and consultations were held with the staff and the management. Afterwards, a satisfaction survey showed that the staff found the actions taken by the company fair and transparent. The consultant continued to follow up on the implementation of the revised hiring practices. In addition, the management received additional training on team management and labour practices.

“It is essential to understand that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Every investment must be analysed individually, and we also need to take into account the rights-holders and the fact that the situation – the context where a company operates – may rapidly change.”

“It is essential to understand that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Every investment must be analysed individually, and we also need to take into account the rights-holders and the fact that the situation – the context where a company operates – may rapidly change.”

– Sylvie Fraboulet-Jussila, Senior Environmental and Social Adviser

More information

Human Rights Statement

Sustainability Policy

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP)

Gender equality

IFC Environmental and Social Performance Standards

ILO Core Labour Standards

Interested to know more about our work in practice?

Climate accounting – our work in practice

Responsible tax principles in practice – our work in practice

Sylvie Fraboulet-Jussila, Senior Environmental and Social Advisor, sylvie.fraboulet-jussila@finnfund.fi, +358 40 587 6467